Walkthrough

In this walkthrough, you will learn about the basic concepts of getML. You will tackle a simple problem using the Python API in order to gain a technical understanding of the benefits of getML. More specifically, you will learn how to do the following:

The guide is applicable to both the Enterprise and the Community editions of getML. The differences between the two are highlighted here.

You have not installed getML on your machine yet? Before you get started, head over to the installation instructions.

Introduction

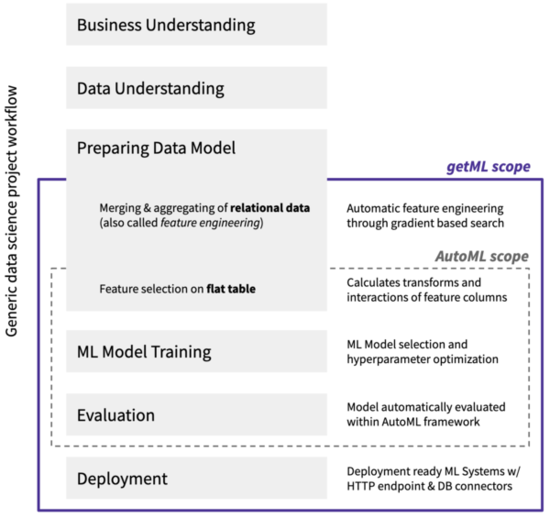

Automated machine learning (AutoML) has attracted a great deal of attention in recent years. The goal is to simplify the application of traditional machine learning methods to real-world business problems by automating key steps of a data science project, such as feature extraction, model selection, and hyperparameter optimization. With AutoML, data scientists are able to develop and compare dozens of models, gain insights, generate predictions, and solve more business problems in less time.

While it is often claimed that AutoML covers the complete workflow of a data science project - from the raw data set to the deployable machine learning models - current solutions have one major drawback: They cannot handle real world business data. This data typically comes in the form of relational data. The relevant information is scattered over a multitude of tables that are related via so-called join keys. In order to start an AutoML pipeline, a flat feature table has to be created from the raw relational data by hand. This step is called feature engineering and is a tedious and error-prone process that accounts for up to 90% of the time in a data science project.

getML adds automated feature engineering on relational data and time series to AutoML. The getML algorithms Multirel, Relboost, and RelMT find the right aggregations and subconditions needed to construct meaningful features from the raw relational data. This is done by performing a sophisticated, gradient-boosting-based heuristic. In doing so, getML brings the vision of end-to-end automation of machine learning within reach for the first time. Note that getML also includes automated model deployment via a HTTP endpoint or database connectors.

All functionality of getML is implemented in the so-called getML Engine. It is written in C++ to achieve the highest performance and efficiency possible and is responsible for all the heavy lifting. The getML Python API acts as a bridge to communicate with the Engine. In addition, the getML Monitor, a graphical web interface available in the Enterprise edition, provides you with an overview of your current projects and pipelines.

In this walkthrough you will learn the basic steps and commands to tackle your data science projects using the Python API. For illustration purpose we will show how an example data set would have been dealt with using classical data science tools. In contrast, we demonstrate on the same example data set how the most tedious part of a data science project - merging and aggregating a relation data set - is automated using getML. By the end of this tutorial you are ready to tackle your own use cases with getML and dive deeper into our software using a variety of follow-up material.

Starting a new project

After you’ve successfully installed getML, you can begin by executing the following in a jupyter-notebook:

import getml

print(f"getML API version: {getml.__version__}\n")

getml.engine.launch() #not needed in docker based installations

"""

Launched the getML Engine. The log output will be stored in

/home/xxxxx/.getML/logs/xxxxxxxxxxxxxx.log.

"""

The getML Monitor, available in the Enterprise edition, is the frontend to the Engine. It should open automatically by launching the Engine. In case it does not, visit http://localhost:1709/ to open it. From now on, the entire analysis is run from Python.

The entry-point for your project is the getml.project module. From here, you can start projects and control running projects. Further, you have access to all project-specific entities, and you can export a project as a .getml bundle to disk or load a .getml bundle from disk. To see the running projects, you can execute:

getml.project

"""

Cannot reach the getML Engine. Please make sure you have set a project.

To set: `getml.engine.set_project(...)`

Available projects:

"""

This message tells us that we have no running Engine instance because we have not set a project. So, we follow the advice and create a new project. All datasets and models belonging to a project will be stored in ~/.getML/projects.

getml.engine.set_project("getting_started")

"""

Connected to project 'getting_started'

"""

getml.project

"""

Current project:

getting_started

"""

Data Set

The data set used in this tutorial consists of 2 tables: (I) the so-called population table represents the entities we want to make a prediction about in the analysis and (II) the peripheral table contains additional information and is related to the population table via a join key. Such a data set could appear, for example, in a customer churn analysis where each row in the population table represents a customer and each row in the peripheral table represents a transaction. It could also be part of a predictive maintenance campaign where each row in the population table corresponds to a particular machine in a production line and each row in the peripheral table to a measurement from a certain sensor.

In this guide, however, we do not assume any particular use case. After all, getML is applicable to a wide range of problems from different domains. Domain specific examples can be found in the notebooks.

population_table, peripheral_table = getml.datasets.make_numerical(

n_rows_population=500,

n_rows_peripheral=100000,

random_state=1709

)

print("Data Frames")

print(getml.project.data_frames)

print("Population table")

print(population_table)

"""

Data Frames

name rows columns memory usage

0 numerical_peripheral_1709 100000 3 2.00 MB

1 numerical_population_1709 500 4 0.01 MB

Population table

Name time_stamp join_key targets column_01

Role time_stamp join_key target numerical

Units time stamp, comparison only

0 1970-01-01 00:00:00.470834 0 101 -0.6295

1 1970-01-01 00:00:00.899782 1 88 -0.9622

2 1970-01-01 00:00:00.085734 2 17 0.7326

3 1970-01-01 00:00:00.365223 3 74 -0.4627

4 1970-01-01 00:00:00.442957 4 96 -0.8374

... ... ... ...

495 1970-01-01 00:00:00.945288 495 93 0.4998

496 1970-01-01 00:00:00.518100 496 101 -0.4657

497 1970-01-01 00:00:00.312872 497 59 0.9932

498 1970-01-01 00:00:00.973845 498 92 0.1197

499 1970-01-01 00:00:00.688690 499 101 -0.1274

500 rows x 4 columns

memory usage: 0.01 MB

type: getml.DataFrame

"""

The population table contains 4 columns. The column called column_01 contains a random numerical value. The next column, targets, is the one we want to predict in the analysis. To this end, we also need to use the information from the peripheral table.

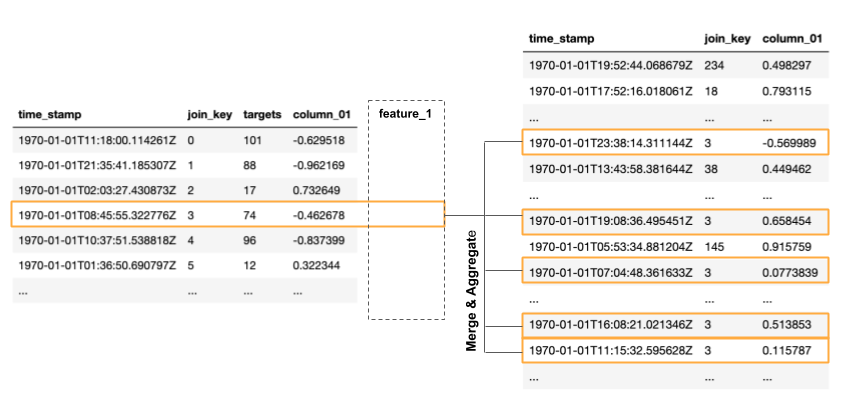

The relationship between the population and peripheral table is established using the join_key and time_stamp columns: Join keys are used to connect one or more rows from one table with one or more rows from the other table. Time stamps are used to limit these joins by enforcing causality and thus ensuring that no data from the future is used during the training.

In the peripheral table, columns_01 also contains a random numerical value. The population table and the peripheral table have a one-to-many relationship via join_key. This means that one row in the population table is associated with many rows in the peripheral table. In order to use the information from the peripheral table, we need to merge the many rows corresponding to one entry in the population table into so-called features. This is done using certain aggregations.

For example, such an aggregation could be the sum of all values in column_01. We could also apply a subcondition, like taking only values into account that fall into a certain time range with respect to the entry in the population table. In SQL code such a feature would look like this:

SELECT COUNT( * )

FROM POPULATION t1

LEFT JOIN PERIPHERAL t2

ON t1.join_key = t2.join_key

WHERE (

( t1.time_stamp - t2.time_stamp <= TIME_WINDOW )

) AND t2.time_stamp <= t1.time_stamp

GROUP BY t1.join_key,

t1.time_stamp;

Unfortunately, neither the right aggregation nor the right subconditions are clear a priori. The feature that allows us to predict the target best could very well be e.g. the average of all values in column_01 that fall below a certain threshold, or something completely different. If you were to tackle this problem with classical machine learning tools, you would have to write many SQL features by hand and find the best ones in a trial-and-error-like fashion. At best, you could apply some domain knowledge that guides you towards the right direction. This approach, however, bears two major disadvantages that prevent you from finding the best-performing features.

- You might not have sufficient domain knowledge.

- You might not have sufficient resources for such a time-consuming, tedious, and error-prone process.

This is where getML comes in. It finds the correct features for you - automatically. You do not need to manually merge and aggregate tables in order to get started with a data science project. In addition, getML uses the derived features in a classical AutoML setting to easily make predictions with established and well-performing algorithms. This means getML provides an end-to-end solution starting from the relational data to a trained ML-model. How this is done via the getML Python API is demonstrated in the following.

Defining the data model

Most machine learning problems on relational data can be expressed as a simple star schema. This example is no exception, so we will use the predefined StarSchema class.

split = getml.data.split.random(train=0.8, test=0.2)

star_schema = getml.data.StarSchema(

population=population_table, alias="population", split=split)

star_schema.join(peripheral_table,

alias="peripheral",

on="join_key",

time_stamps="time_stamp",

)

Building a pipeline

Now we can define the feature learner. Additionally, you can alter some hyperparameters like the number of features you want to train or the list of aggregations to select from when building features.

fastprop = getml.feature_learning.FastProp(

num_features=5,

aggregation=[

getml.feature_learning.aggregations.COUNT,

getml.feature_learning.aggregations.SUM

],

)

Pipeline objects. In addition to the Placeholders representing the DataFrames you also have to provide a feature learner (from getml.feature_learning) and a predictor (from getml.predictors). pipe = getml.pipeline.Pipeline(

data_model=star_schema.data_model,

feature_learners=[fastprop],

predictors=[getml.predictors.LinearRegression()],

)

Note

For the sake of demonstration, we have chosen a narrow search field in aggregation space by only letting FastProp use COUNT and SUM, we use a simple LinearRegression and construct only 5 different features. In real world projects you have little reason to artificially restrict your aggregation set and would use something more straightforward like aggregation=getml.feature_learning.aggregations.FASTPROP.default, you would construct at least 100 features and you could consider using a more powerful predictor to get results significantly better than what we will achieve here.

Working with a pipeline

Now, that we have defined a Pipeline, we can let getML do the heavy lifting of your typical data science project. With a well-defined Pipeline, you can, i.a.:

fit()the pipeline, to learn the logic behind your features (also referred to as training);score()the pipeline to evaluate its performance on unseen data;transform()the pipeline and materialize the learned logic into concrete (numerical) features;predict()thetargets for unseen data;deploy()the pipeline to an http endpoint.

Training

When fitting the model, we pass the handlers to the actual data residing in the getML Engine – the DataFrames.

pipe.fit(star_schema.train)

"""

Checking data model...

Staging... 100% ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ • 0:00:00 • 0:00:00

Checking... 100% ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ • 0:00:00 • 0:00:00

OK.

Staging... 100% ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ • 0:00:00 • 0:00:00

FastProp: Trying 5 features... 100% ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ • 0:00:00 • 0:00:00

FastProp: Building features... 100% ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ • 0:00:00 • 0:00:00

LinearRegression: Training as predictor... 100% ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ • 0:00:00 • 0:00:00

Trained pipeline.

Time taken: 0h:0m:0.023915

Pipeline(data_model='population',

feature_learners=['FastProp'],

feature_selectors=[],

include_categorical=False,

loss_function='SquareLoss',

peripheral=['peripheral'],

predictors=['LinearRegression'],

preprocessors=[],

share_selected_features=0.5,

tags=['container-cjCqZq'])

"""

That’s it. The features learned by FastProp as well as the LinearRegression are now trained on our data set.

Scoring

We can also score our algorithms on the test set.

pipe.score(star_schema.test)

"""

Staging... 100% ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ • 0:00:00 • 0:00:00

Preprocessing... 100% ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ • 0:00:00 • 0:00:00

FastProp: Building features... 100% ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ • 0:00:00 • 0:00:00

date time set used target mae rmse rsquared

0 2024-08-08 12:14:11 train targets 3.3721 4.1891 0.9853

1 2024-08-08 12:21:35 test targets 3.7548 4.7093 0.981

"""

Our model is able to predict the target variable in the newly generated data set pretty accurately. Though, the enterprise feature learner Multirel performs even better here with R2 of 0.9995 and MAE and RMSE of 0.07079 and 0.1638 respectively.

Making predictions

Let’s simulate the arrival of unseen data and generate another population table. The data model is already defined and the pipeline trained. All we need to do is to add data to a Container and pass it to the existing pipe object.

population_table_unseen, peripheral_table_unseen = getml.datasets.make_numerical(

n_rows_population=200,

n_rows_peripheral=8000,

random_state=1711,

)

container_unseen = getml.data.Container(population_table_unseen)

container_unseen.add(peripheral=peripheral_table_unseen)

yhat = pipe.predict(container_unseen.full)

print(yhat[:10])

"""

Staging... 100% ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ • 0:00:00 • 0:00:00

Preprocessing... 100% ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ • 0:00:00 • 0:00:00

FastProp: Building features... 100% ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ • 0:00:00 • 0:00:00

>>> print(yhat[:10])

[[ 4.16876676]

[17.32933 ]

[26.62467516]

[-5.30655759]

[27.4984785 ]

[21.48631811]

[18.16896219]

[ 5.2784719 ]

[20.5992354 ]

[26.20538556]]

"""

Extracting features

Of course, you can also transform a specific data set into the corresponding features in order to insert them into another machine learning algorithm.

features = pipe.transform(container_unseen.full)

print(features)

"""

Staging... 100% ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ • 0:00:00 • 0:00:00

Preprocessing... 100% ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ • 0:00:00 • 0:00:00

FastProp: Building features... 100% ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ • 0:00:00 • 0:00:00

[[-7.14232213e-01 2.39745475e-01 2.62855261e-01 1.28462060e-02

5.00000000e+00 -3.18568319e-01]

[-1.17601634e-01 3.42472663e+00 3.61423201e+00 3.24305583e-02

1.40000000e+01 3.94656676e-01]

[-2.48645436e+00 1.27495266e+01 1.33228011e+01 1.99520872e-02

3.60000000e+01 1.24700392e-01]

...

[ 9.55124379e-01 9.16437833e-01 9.40897830e-01 2.73040074e-02

8.00000000e+00 -7.49963688e-01]

[-3.56023429e+00 3.37346772e+00 2.11562428e+00 2.53698895e-02

1.50000000e+01 -7.27880243e-01]

[ 2.72804029e-02 2.87302783e-02 5.36035230e-02 2.77103542e-02

2.00000000e+00 -3.53700424e-01]]

"""

If you want to see a SQL transpilation of a feature's logic, you can do so by clicking on the feature in the Monitor (Enterprise edition only) or by inspecting the sql attribute on a feature. A Pipeline's features are held by the Features container. For example, to inspect the SQL code of the feature with the highest importance, run:

pipe.features.sort(key=lambda feature: feature.importance, descending = True)[0].sql

That should return something like this:

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS "FEATURE_1_5";

CREATE TABLE "FEATURE_1_5" AS

SELECT COUNT( * ) AS "feature_1_5",

t1.rowid AS rownum

FROM "POPULATION__STAGING_TABLE_1" t1

INNER JOIN "PERIPHERAL__STAGING_TABLE_2" t2

ON t1."join_key" = t2."join_key"

WHERE t2."time_stamp" <= t1."time_stamp"

GROUP BY t1.rowid;

This very much resembles the ad hoc definition we tried in the beginning. The correct aggregation to use on this data set is COUNT. getML extracted this definition completely autonomously.

Next steps

This guide has shown you the very basics of getML. Starting with raw data, you have completed a full project including feature engineering and linear regression using an automated end-to-end pipeline. The most tedious part of this process - finding the right aggregations and subconditions to construct a feature table from the relational data model - was also included in this pipeline.

But there’s more! Examples show application of getML on real world data sets.

Also, don’t hesitate to contact us with your feedback.